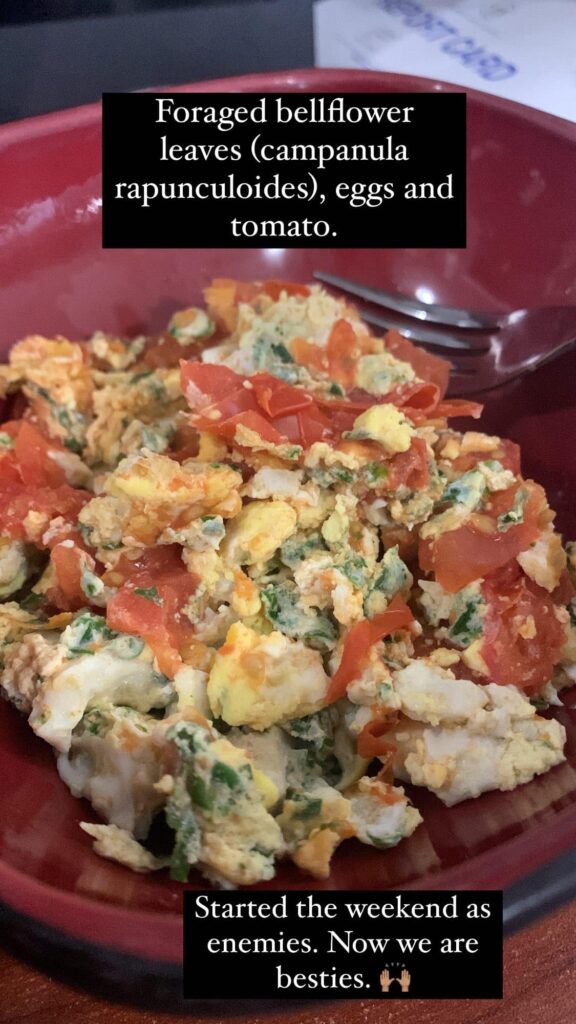

Been a while since we posted!! Life has been crazy preparing the garden beds and trying to keep our plants alive! Here’s a little story about an enemy turned friend haha. As they say in permaculture the problem is the solution.

Here is Creeping Bellflower – Campanula rapunculoides.

A wildflower that is invasive and is likely right in your own yard! Identifying it is pretty easy! Definitely, an easy green to forage for and is quite prolific, which means there are lots to harvest!

What Is Creeping Bellflower (Campanula Rapunculoides)?

Plant type: perennial

Size: low growing clumped foliage in spring, grows to 1 m tall flowering spike in early summer

Leaves: heart-shaped in early-stage becoming lance-shaped, tooth-edged, and coarse-textured (a tad hairy!)

Flowers: purple-blue 2-3 cm long nodding bells, blooms begin on lower stem

Bloom season: June – October

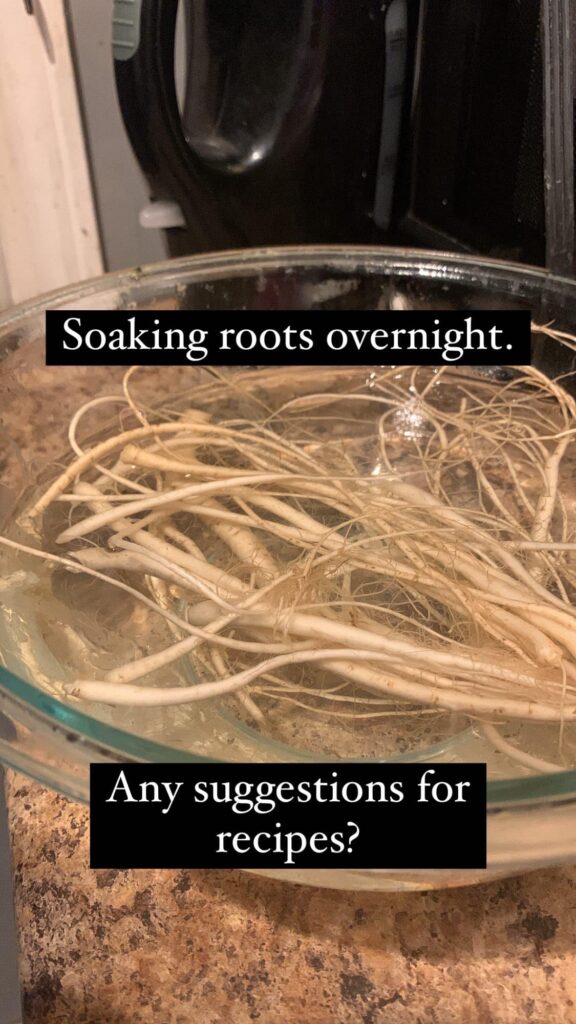

Now the roots can be a pain. Creeping bellflower has both a thick, tuber-like root that’s an inch or up to several inches deep in the soil (which can be why they take over a raised garden bed). Aside from these tuber-type roots it also has a lot of thread-like little roots that grow horizontally just below the soil. As this was the issue in our raised beds I got to know the roots quite well. I was so frustrated by these roots, I started Googling solutions to dealing with them and after some research, I found out, that it’s edible!! As the permies say, try to turn the problem, into the solution!!

What Does Creeping Bellflower Taste Like?

The greens are very similar to spinach. The taste is subtle and not bitter or too strong which I find is typical of wild edible greens. This makes it a top option to use as a spinach alternative. The one thing I will mention is that the leaves have a bit of a fuzzy texture and I think is much better cooked (but they can totally be eaten raw! I used it like spinach in eggs and then the roots I soaked and made into a Korena side dish called, Doraji Namul! Check the recipe I used below! I can also see the greens being used in pesto and even using the roots as s substitute for the pine nuts!! We will be trying that in another post.

How To Make Doraji Namul (Sauteed Bellflower Root)

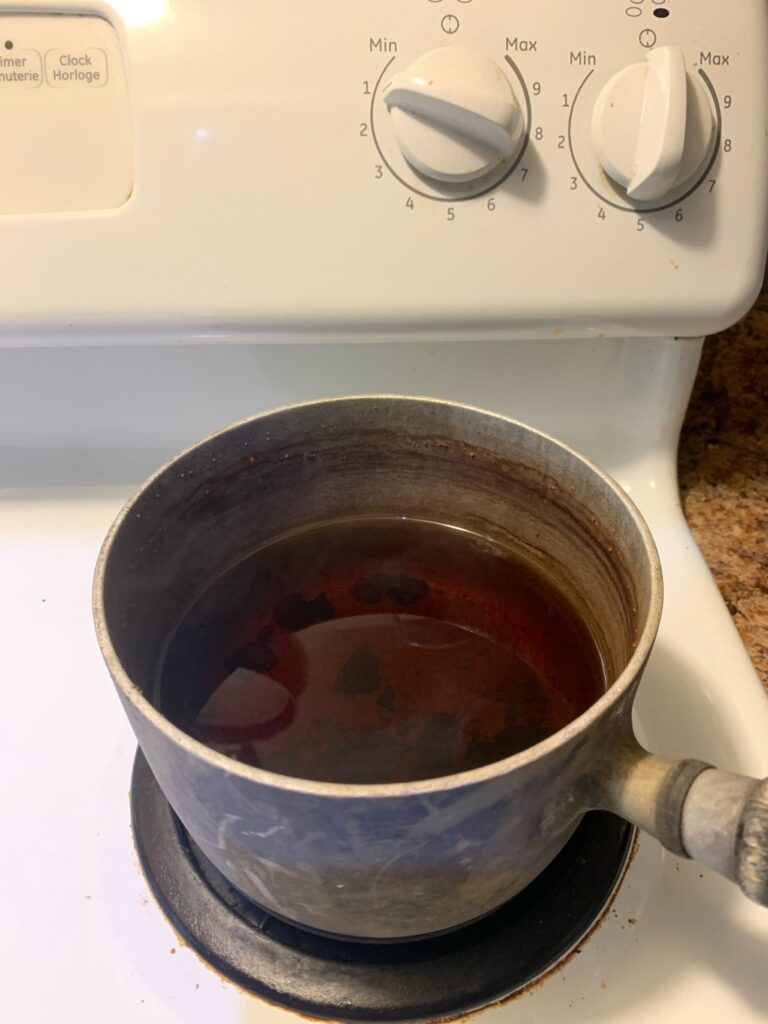

For our recipe, I used fresh roots, so I made sure to soak them overnight in saltwater to cut some of the bitterness. If you can find dried roots you can use them as well!!

- If using dried roots. Place the doraji / bellflower root in a large bowl and immerse it in water overnight (8 to 12 hours). Drain the water. If using fresh like in my case, simply add the coarse sea salt and wash the bellflower root a few times with running water. This is to remove the bitter taste of the bellflower root. Boil some water in a saucepan (enough to cover the root) and blanch the bellflower root in rolling boiling water for about 2 minutes. Drain the water and rinse under cold running water. (I actually boiled them for a little longer until they were softened).

- Place the blanched bellflower root in a mixing bowl then add the seasoning sauce. Mix them well with your hands.

- Heat up a skillet over medium-high heat. Once heated, spread the cooking oil. Add the seasoned bellflower root and stir around quickly. Add the green onion and sesame seeds. Remove from the heat. Serve.

Be sure to look around as foraging has begun!!

Sometimes life’s toughest challenges can secretly be a blessing in disguise!

It’s all about perspective.